Sept. 25, 2018

By: Michael Feldman

A report conducted by the World Economic Forum (WEF) has found that machines are rapidly replacing human labor across all major industries. That offers both good news and bad news for workers and the companies that employ them.

The Future of Jobs Report 2018 looks at various workforce trends being driven by what the WEF refers to as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Collectively, this revolution is being enabled by four specific technology categories: artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, cloud computing, and ubiquitous high-speed mobile internet. According to the employers surveyed by the WEF, these four categories are expected to exert major changes to the global workforce from now until 2022.

The Future of Jobs Report 2018 looks at various workforce trends being driven by what the WEF refers to as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Collectively, this revolution is being enabled by four specific technology categories: artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, cloud computing, and ubiquitous high-speed mobile internet. According to the employers surveyed by the WEF, these four categories are expected to exert major changes to the global workforce from now until 2022.

In general, the companies surveyed for the report concluded that these four technologies would result in a net positive for both business growth and an overall increase in demand for workers. The anticipation of business growth is not a big revelation, inasmuch as these technologies are designed to increase productivity and efficiencies with regard to existing work (think AI-enabled medical diagnosis) while enabling new kinds businesses to emerge (think self-driving car services).

Perhaps the biggest surprise is the projected workforce churn. When the WEF authors crunched the numbers, they determined that 75 million jobs may be displaced over the next four years. But while that was happening, 133 million additional jobs could also emerge. These were based on new job roles, like data scientists, AI specialists, and human-machine interaction designers. Jobs that would be most susceptible to displacement include data entry clerks, accountants, vehicle drivers, and customer service workers.

Even if those encouraging workforce numbers hold up, the challenge will be to shift all of those displaced workers into newer roles, something companies have not been particularly good at doing on their own. The problem is exacerbated by the fact that many of the threatened jobs are based on manual labor, while many of the newer jobs require a significant investment in training.

There’s definitely some nuance here. The report points out that often the jobs themselves are not eliminated, but only certain tasks within the job become automated. One recent study noted that almost two-thirds of jobs include at least 30 percent of tasks that could be automated with current technology, but only about a quarter of jobs can be automated at a level above 70 percent.

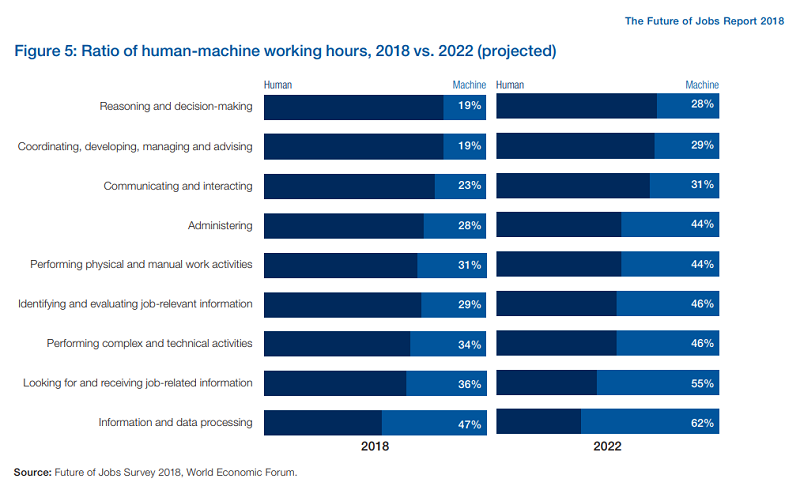

As a result, automation may change the nature of the work, but it won’t displace the workforce en masse. Moreover, by automating repetitive tasks, workers are able to use more of their time for high-level activities, making them more valuable to their company. The figure below from the WEF report illustrates the breakdown between human and machine working hours for various types of tasks and how it’s projected to change between 2018 and 2022.

Overall, about 71 percent of the total task hours across the industries covered in the report are currently performed by human beings, compared to 29 percent performed by machines. The WEF projects that by 2022 this average is expected to shift to to 58 percent for humans and 42 percent for machines. Although the report doesn’t extend this projection past the four-year timeframe, clearly the human-machine crossover point is quickly approaching.

Whether a worker’s job is just rewired by automation or is eliminated altogether, employers will have to come to grips with retraining. According the report, the companies surveyed believe at least 54 percent of employees will require “significant reskilling and upskilling.” Of these, about 35 percent are expected to need retraining of 1 to 6 months, 9 percent will require retraining of 6 to 12 months, and 10 percent will require retraining of more than a year.

The report notes that currently only about 30 percent of employees with jobs most susceptible to displacement have received any kind of retraining over the past year. These workers are also much less likely to have participated in any on-the-job training, distance learning, or any type of formal education compared to their more highly skilled co-workers (whose jobs tend to be less susceptible to the effects of automation). The WEF authors point to a number of possible approaches to improving the retraining landscape, including getting employers to work in tandem with the government and educational institutions in order to deal with this anticipated workforce disruption.

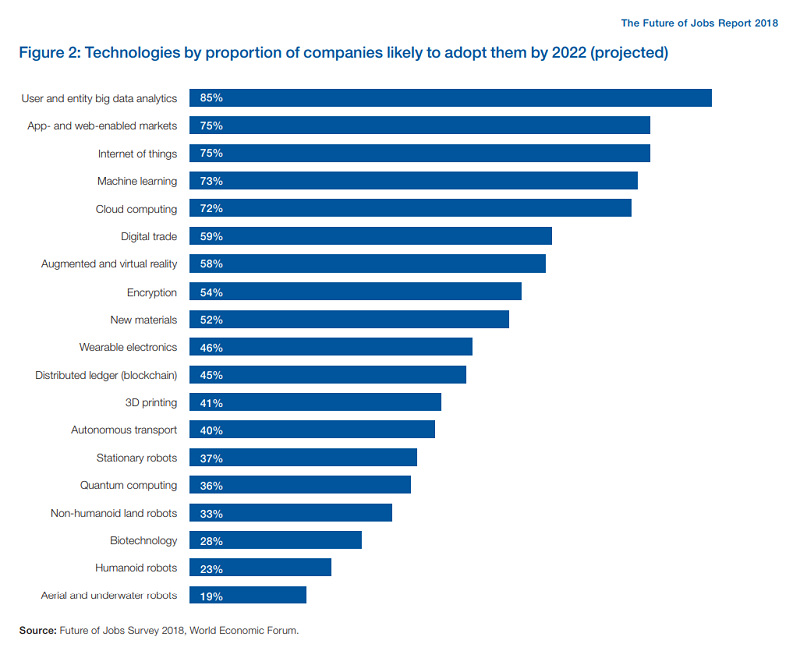

Based on the survey data, the WEF report also projected the likely adoption rates of the various technologies associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which is illustrated in the figure below. It shows the usual suspects at the top, namely data analytics, apps/the web, the internet of things, machine learning, and cloud computing. Here it’s interesting to note that companies are projected to adopt machine learning and cloud computing at nearly identical rates by 2022, even though cloud computing predated machine learning by more than a decade. It’s also surprising to see such a low adoption rate for biotechnology until you realize that the vast majority of companies are not involved in biotech products or services. In fact, the more generic but futuristic technology of humanoid robots is expected to be adopted at only a slightly lower rate than biotechnology by 2022.

The WEF write-up also slices the data across all the major industries and geographies, offering a more granular picture of how these emerging technologies are impacting different enclaves. If you’re interested in the details, you can download the entire report here.